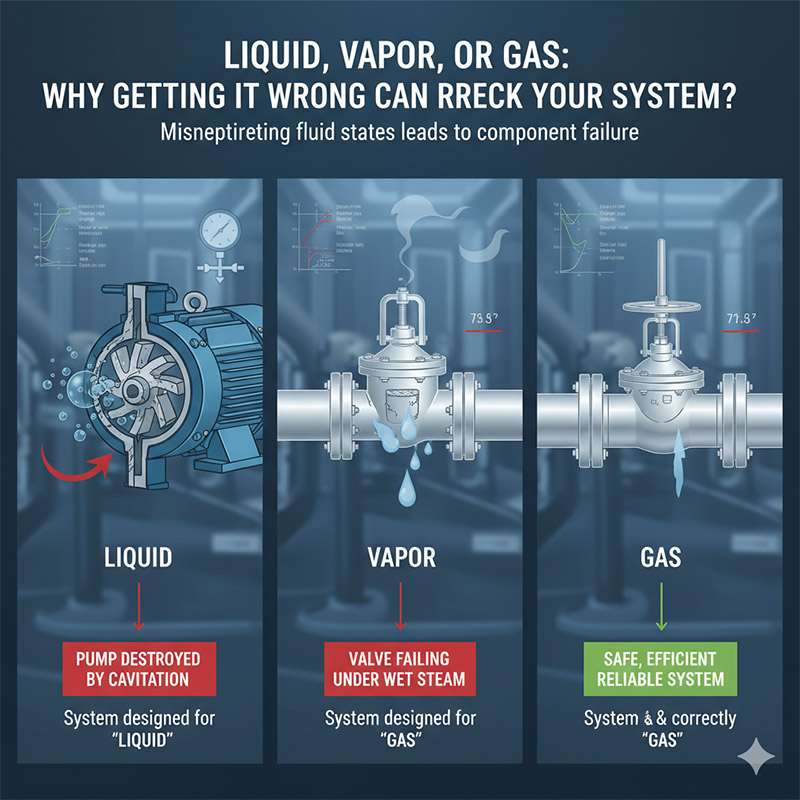

Liquid, Vapor, or Gas: Why Getting It Wrong Can Wreck Your System?

You designed your system for a "liquid," but the pump is getting destroyed by cavitation. Or you specified a valve for a "gas," but it's failing under wet steam.

This happens when we misinterpret the state of the fluid. Understanding the critical, practical differences between a liquid, a vapor, and a gas is not academic—it's essential for designing a system that is safe, efficient, and reliable.

Early in my career, I saw a maintenance team replace the same expensive pump three times in six months. It kept failing with a horrible grinding noise. The system was designed to move hot water. The problem wasn't the pump's quality; it was a design flaw. A valve upstream was causing a slight pressure drop. This pressure drop was just enough to make the hot water boil inside the pipe, turning a small fraction of it into vapor bubbles. When these bubbles hit the high-pressure side of the pump, they collapsed violently. This phenomenon, called cavitation, was acting like a tiny sandblaster, eating away at the pump's impeller. The engineer had designed for a liquid, but in reality, they had a mix of liquid and vapor. That small oversight cost them thousands.

When is a Liquid Not Just a Simple Liquid?

You assume a liquid is stable and incompressible. But a sudden pressure drop in your pipeline causes it to flash into vapor, starving a pump or choking a valve.

A liquid's state is a delicate balance of temperature and pressure. Even a "cold" liquid can boil if the pressure drops low enough. Understanding its vapor pressure is key to preventing cavitation and ensuring stable flow.

We learn in school that water boils at 100°C (212°F). That's only true at sea-level atmospheric pressure. If you're on a mountain, the pressure is lower, and water boils at a lower temperature. The same principle applies inside a pipe. Every liquid has a "vapor pressure," which is the pressure at which it will start to boil at a given temperature. If the pressure in your system drops below the liquid's vapor pressure, the liquid will spontaneously flash into vapor bubbles. This is the root cause of cavitation, which can destroy a pump in hours. An experienced designer like Jacky knows to check the vapor pressure of his fluid at the operating temperature and ensure the system pressure always stays well above that value, especially around pumps, valves, and other restrictions. A liquid that is far from its boiling point is called a "subcooled liquid." A liquid right at its boiling point is a "saturated liquid"—and that is the danger zone.

The Pressure and Temperature Dance

-

### Vapor Pressure is Your Enemy This is the most critical property to understand for any liquid handling system. It's the "boiling line" you must not cross by letting your system pressure drop too low.

-

### Subcooled vs. Saturated A subcooled liquid is stable and predictable. A saturated liquid is on a knife's edge, ready to flash into vapor with the slightest pressure change. Always design for a subcooled state.

| Condition | System Pressure | Liquid State | Engineering Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safe Operation | >> Vapor Pressure | Subcooled Liquid | Low (Stable) |

| Danger Zone | ≈ Vapor Pressure | Saturated Liquid | Critical (Risk of Cavitation) |

| Flashing | < Vapor Pressure | Liquid + Vapor Mix | High (System Failure) |

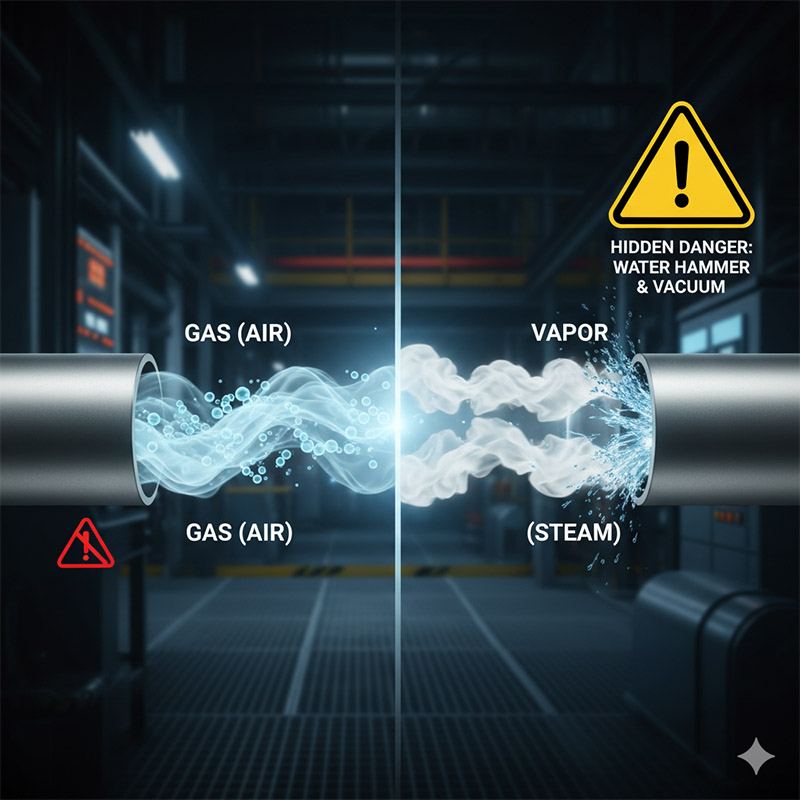

Why is Vapor the "Hidden Danger" Compared to a Gas?

You treat steam and compressed air as the same "gas." But when steam cools, it collapses back into water, creating a vacuum or a destructive water hammer effect.

The critical difference is condensability. A vapor, like steam, is a gas that is close to its condensation point. A true gas, like air, is not. This means vapors can undergo a rapid, dramatic phase change back to liquid inside your system.

This is the most misunderstood concept, and it has massive safety implications. Let's compare steam (a vapor) and nitrogen (a gas). Both are invisible, compressible fluids. But steam is just water in its gaseous state, and it's not far from becoming water again. If you inject 1 cubic foot of steam into a cold pipe, it will rapidly cool and condense, collapsing into about 1 cubic inch of water. This 1700:1 volume reduction creates a massive vacuum that can crush pipes. It can also cause "steam hammer," where slugs of condensed water are accelerated to high speeds and slam into fittings. Nitrogen, on the other hand, is a "true" gas at any normal industrial temperature. Its boiling point is -196°C. It will not condense into liquid in your pipes. The technical difference lies in their relation to the "critical point." A vapor is a gas below its critical temperature; a gas is above it. For you, the practical difference is simple: vapors can kill your system by suddenly turning back into liquid.

The True Identity of a Gas

-

### Vapor: The Condensable Gas Think of a vapor as a gas that wants to be a liquid. Small changes in temperature or increases in pressure can make it condense. Steam is the classic example.

-

### Gas: The Stable Gas Think of a true gas as one that is very far from its liquid state under your operating conditions. Air, nitrogen, and oxygen are common examples. It will not liquefy in your system.

| Property | Vapor (e.g., Steam) | Gas (e.g., Nitrogen) |

|---|---|---|

| State | Gaseous, but below its critical temp. | Gaseous, and above its critical temp. |

| Condensability | Easily condenses with cooling/pressure. | Will not condense in normal conditions. |

| Volume Change | Huge and rapid during phase change. | Stable and predictable (follows gas laws). |

| Primary Risk | Water hammer, vacuum collapse. | Over-pressurization. |

Conclusion

Mastering the states of matter is key to flawless system design. By respecting the unique behaviors of liquids, vapors, and gases, you can prevent failures and ensure robust, safe operation.